Engineering principles of Tarantool

This is the second part of a four-part transcript of my talk at Highload conference 2015. For the design part, see my previous post.

At this conference, there will be a talk on a DBMS named ChronicleMap. An interesting thing about ChronicleMap is that the engineers were trying to achieve 1 ms latency for a database update. Their primary goal was to make updates take significantly less time than in any other database. In achieving this goal, the engineers were ready to potentially throw more hardware at the problem than was necessary to simply sustain their update rate: the latency was paramount, not just the RPS.

In our case, the situation is somewhat different. And we resolve the speed-efficiency tradeoff based on different priorities. Let me elaborate on this a bit. Suppose you need to get to a conference venue, and there is zero traffic - what will you take then? A taxi, and this will be the fastest option. Or public transport, and this will be the cheapest option. Public transport is cheap since it spreads the total cost across many passengers. “Box-carring” occurs, that is you share operational costs with all the others. And that’s the case with Tarantool.

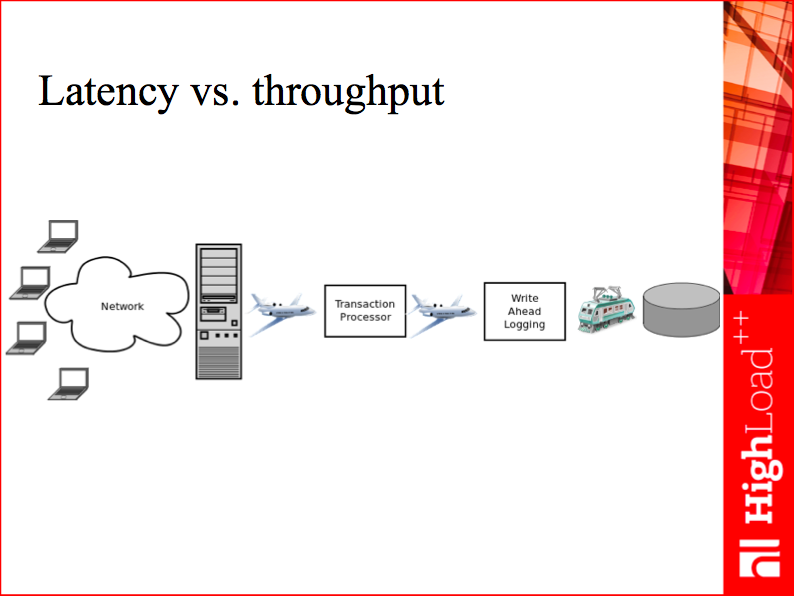

While other DBMSs strive for, say, very low latency but probably not the highest possible throughput, we realized that from an end user’s perspective, network latency dominates over RAM access latency, and optimized the system to produce maximal throughput while keeping the latency proportional to a typical network access, a few milliseconds per request. Let’s now put it in engineering terms.

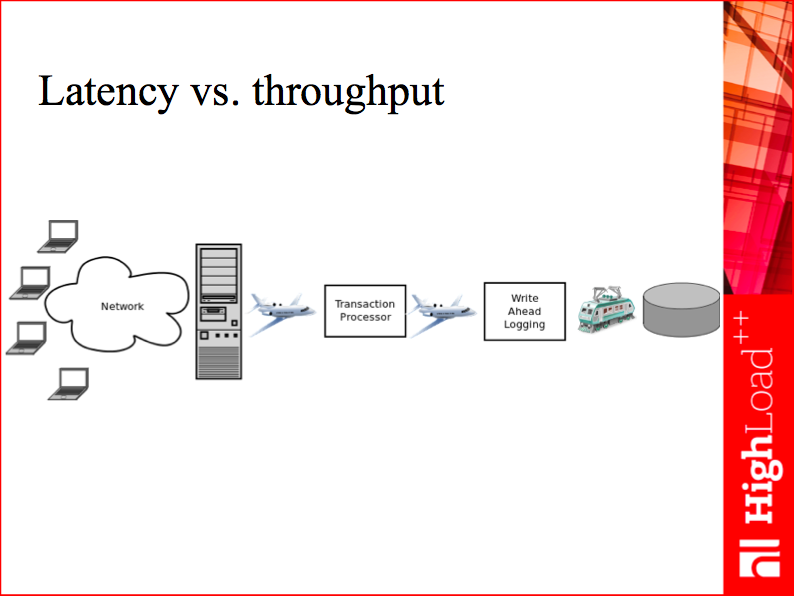

First off, the network is not only slow, it is expensive to use: despite living in the age of containers and unikernels, we still use operating system APIs designed in times when network bandwidth was measured in kilobytes per second. As a result, every time we need to address the network, we must pass control to the operating system, paying the hefty price of a system call. This is why, to work with network, Tarantool uses a dedicated operating system thread. Next, while modern HDDs are widely known to be “slow”, their bandwidth has improved dramatically, and may well use up a dedicated thread to saturate, especially if data is compressed. The write-ahead logging in Tarantool is also done in a dedicated thread. Finally, we have a thread for transaction processing, executing transactions one after another. These three threads form a pipeline, with every query passing through it during execution. Having a pipeline, we need an efficient way of minimizing its standstill time.

Imagine there is only one request in the pipeline at a time. The request is first handled by the network thread, the other two threads standing still. Then it’s passed to the transaction processor thread, the other two threads standing still. And so on. Overall, we need to bounce a request 4 times during its lifetime: to and from the network thread, to and from the write-ahead log thread, perform two network I/O operations and one disk I/O. Assuming there are 4 context switches and a dozen of system calls per request, and the average cost is thousands of nanoseconds per context switch and hundreds of nanoseconds per system call, we’d pay a price of about 10,000 ns per request! This is only 100,000 requests per second, with 3 CPU cores fully used. But now imagine there are many clients and maybe a hundred requests in the pipeline at any given moment in time. We pay the same 10,000 ns price, but now it is shared by 100 requests, since we still perform the same number of context switches and system calls. This is only 100 ns of overhead per request, less than the cost of a single system call, and some 10-100 times less than the overhead of a traditional database.

To achieve such throughput, we designed an asynchronous client/server protocol that extends the pipeline all the way up to the client: with it, we can use a single TCP connection to read requests from multiple clients and to reply to all clients at once. That said, every client receives their reply as soon as it’s ready, without waiting for previous queries on the socket to complete. This strategy allows us to enjoy the lowest cost possible incurred by a single request, and provide lower latency than multi-threaded solutions while using only a single thread to execute transactions.

While the idea of box-carring and shared costs looks simple, we needed a practical way of handling hundreds of simultaneous requests within 3 dedicated threads. An approach to concurrency that would pack many virtual threads of execution into one physical thread, and do so without turning the already complicated task of database implementation into a plate of spaghetti.

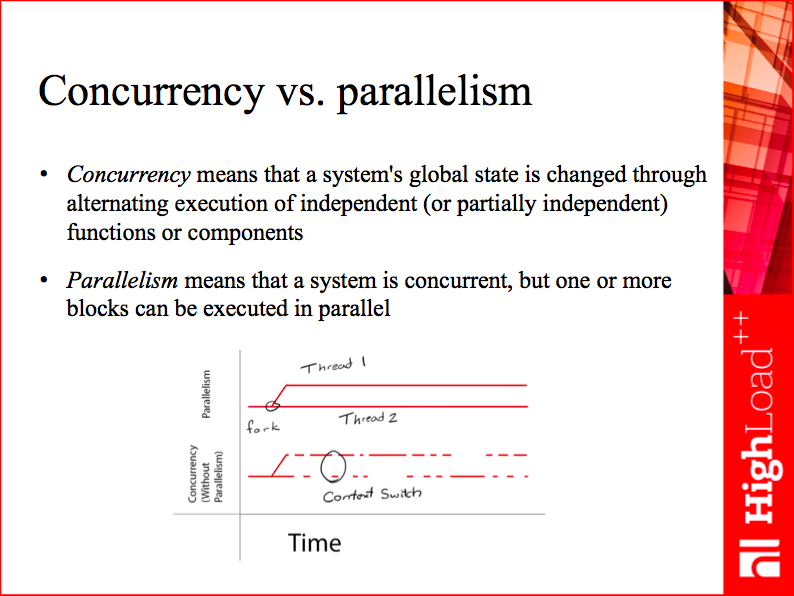

Generally, the following approaches to parallel programming exist:

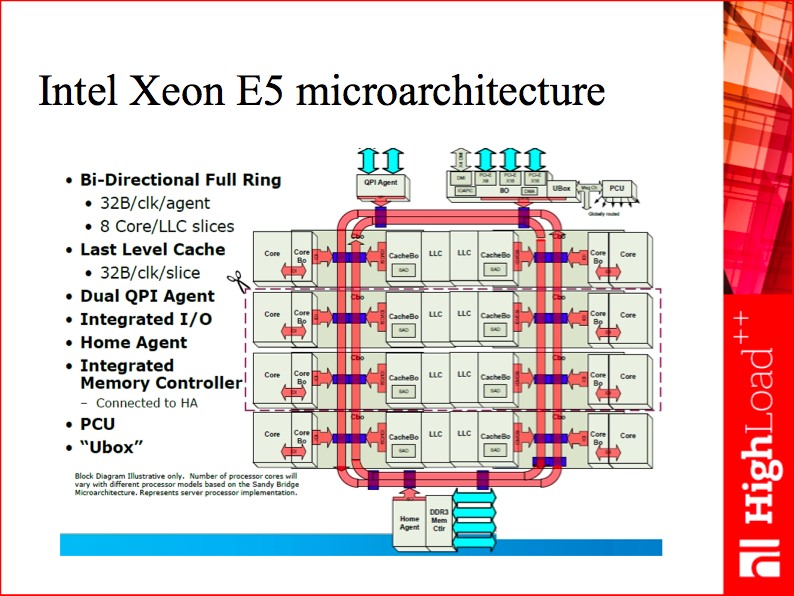

When choosing a method for inter-thread information exchange, one should take into consideration not only the costs considered above (memory access, disk access, network access, which are performed explicitly), but such subtle matters as how often the processor has to flush the L1 or L2 or CPU cache.

Between tiny L1 and L2 caches and the enormous RAM, we have from 16 to 32 MB of the L3 cache distributed among all the CPU cores. So, the more efficiently we use the L3 cache, the better our system performs.

These things are implicit, there is no programmatic way to control them, so a programmer is flying blind: you change a paradigm – the cache starts working a tad better, the performance grows a bit, but there is no way of knowing for sure why exactly.

Keeping these considerations in mind, let’s evaluate the alternatives I listed on the slide. Some of them I discard right away: hardware transactional memory is not widespread, and wait-free algorithms, while capable of improving on some of the problems of lock-based programming, are heavily using interlocked CPU instructions, which do not play nicely with the CPU cache. So, effectively, there are 3 choices: lock-based, actor-based and functional programming. Jumping ahead, let me say that we chose the last approach on the list, the actor model. You might be wondering why, so please bear with me - I’ll get to that eventually.

Let’s take a look at what’s wrong with locking. I’ve been developing with

mutexes for all my waking life, and they are a great instrument.

Unfortunately, programming with mutexes suffers from a serious drawback,

which usually only reveals itself after hundreds of thousands of lines of

code are written and the software is mature. This drawback is called the

composability problem. Here’s an example. Suppose you have a critical

section in a concurrent data structure used by a lot of threads. So, you

take this critical section and encapsulate it in some method - let’s call it

insert(). Time goes by, you have a lot of code working with the critical

section, so you introduce a macrostructure that uses the concurrent data

structure and encapsulates some of the less trivial business logic of your

application. Some time later you discover that some of the methods of this

macrostructure must be used from within a critical section, that is, it

should be concurrent too. You end up having a critical section within a

critical section. The problem is that with locking, you need to think twice

before allowing that to happen. Why is that? The risk here is to get not

only - you guessed it - deadlocks, but also less trivial problems, such as

hotspots, lock convoying, thread priority inversion and so on.

Deadlock is essentially a mutual wait cycle. Suppose we use locks in the order A, B in one place in the code, but in the other place we use these locks in the order B, A, and - lo and behold - we’re getting a deadlock under workload. Wait-free algorithms solve this one problem – the problem of deadlocks. These algorithms don’t get deadlocked, because they don’t wait. But they don’t solve other problems related to locking-based algorithms.

It’s also worth exploring the issues hiding behind the terms lock convoy and hotspot. They have to do in part with wait-free algorithms as well. Suppose you’ve written a program with a critical section assuming that it works with two threads: a producer thread and a consumer thread; the workload is about 1,000 requests per second, so both these threads execute the critical section 1,000 times per second. Everything’s working fine. But then your situation changes. You get new hardware, or the threads are now doing a different job, or the environment changes - whatever. This example is about composability, so you start extending and fine-tuning your system, and your critical section suddenly becomes “hot”. Suppose it’s some minor job like updating two variables within the critical section, but now, instead of being called 1,000 times per second, it’s called 10,000 or 100,000 times per second so that multiple requests are constantly competing for access to this critical section, with threads being blocked or suspended and so on.

You can try adjusting the priorities or the execution order, that is treating requests as high- or low-priority. As a result, high-priority requests to the critical section may oust low-priority ones, which would mean low-priority requests are never executed - that’s known as starvation.

Lock convoy refers to the situation when you have a minor critical section inside a major one so that it becomes impossible to access the minor section.

There’s a wide variety of situations, all leading us to the same conclusion: locks are not composable. If your system is based on locking, and that’s your main programming primitive, you can hardly scale it.

To conclude, with locking you simply cannot freely use the code with multiple critical sections in it, because it loses basic development properties like the ability to encapsulate and decompose problems into smaller ones.

There were others who were aware of these problems long before me, like those who created Erlang some 30-40 years ago. Generally speaking, Erlang would have been an ideal instrument for developing Tarantool.

Indeed, functional programming is an approach that can solve the composability problem. In this paradigm, critical sections are not defined explicitly, but added by the compiler and the runtime of a functional language. And the language has enough information to do the job, since all dependencies between functions and data are expressed explicitly in the program. In other words, you never need to acquire locks, but if you have a function that is functionally dependent on another function, the language can parallelize its execution transparently for the function’s author. You have no shared data, so you have no conflicts caused by it.

The trouble with this approach is that it explicitly prohibits use of shared data. And a database is the very kind of application whose goal is to provide concurrent access to a shared data structure.

Besides, there are no development environments today that would allow us to apply the functional approach to system programming.

These considerations explain our choice of the actor model - a paradigm that allows access to shared data structures, yet is composable and with which we could keep development costs low.

In the actor model, participants access each other’s private state by exchanging messages. We created our own actor runtime, beginning with a single thread. Within a single thread, we run many fibers - independent lines of execution, which cooperatively utilize a single CPU core by deliberately yielding control to each other. Each fiber within a single thread represents an actor. They can access this thread’s shared data without locks, and exchange messages with fibers within the same thread or in other threads. Message exchange within a thread is easy - one could have a global data structure used by all the participants.

A more serious problem is how to deliver messages to actors in other threads. To understand our solution, let’s get back to the Latency vs. throughput slide with public transport as an example.

Here we have a network thread, a transaction processor thread, a write-ahead logging thread and a virtual entity for every request in every thread – an actor. An actor’s task in the network thread is to get a request, parse it, check it for correctness and send an execute this request message to the transaction processor. In its turn, a peer actor in the transaction processor takes the request (let’s imagine it’s an insert statement), checks the database for duplicate keys and constraint violations, executes the involved Lua functions and triggers, reads or changes the data as requested and says OK to the corresponding buddy in the write-ahead log thread that writes the transaction log entry to disk.

If we followed exactly this procedure, we’d be exchanging messages for each request. But our goal is to minimize this activity: in our paradigm, we do want actors in our program to exchange messages, but with minimal messaging costs, by using a multiplexing message exchange. That’s where the cooperative multitasking approach we took to scheduling multiple actors within a single thread comes in handy, as it allows encapsulating message exchange into fiber scheduler events. Every time an actor sends a message to a peer in a different thread, it suspends its own execution and yields control to the next actor of its own thread, until a response to the message has arrived. Thus, we use coroutines to maintain continuous activity in each thread, while constantly switching control between the actors.

This trick represents to me a focal point of Tarantool design. I even put a cute hypercube on the Actor model slide above, where I’m trying to stress the importance of low-cost message exchange. A very special property of a hypercube is that the number of connections inside of it grows proportionally to the number of nodes, not quadratically. Similarly, the cost of our message exchange is proportional to the number of physical operating system threads, but does not depend on the number of actors: within a given configuration with fixed number of threads, all actors share a fixed cost of the operating system overhead for message exchange.

It’s funny that some of the earliest supercomputers - for example, Cray - were also using the idea of hypercube to put maximal compute power into a limited physical space. Another example demonstrating the same principle is a regular mechanical telephone switch, which was able to efficiently multiplex many interacting entities using a two-, and later three-dimensional board of circuits. People who created these engineering marvels were great minds of spatial design!

The reason why I chose a four-dimensional, and not three-dimensional hypercube as an illustration is that Tarantool repeats the same design pattern for communication on multiple levels: within a single thread, between multiple threads, between shards on a single machine, and between multiple machines of a compute grid. On all these levels, the message exchange cost dominates the compute cost, as the number of routes is equal to the number of participants, squared. So, minimizing the expense of message exchange is paramount.

Going back to the difficult problem of efficient utilization of the L3 cache, this model is also pretty good for it. Let’s take a look at a typical CPU chip. The big thing in the middle is its L3 cache:

Side note: Back in the day, there were vigorous debates between advocates of the CISC and RISC architectures. Nowadays, while I’m a big fan of the ARM architecture, arguing about the instruction set alone sounds ridiculous to me. Just take a look at the illustration to see how much physical space of a chip is taken by the L3 cache.

With locking, every time we need to send a message, that is to synchronize two concurrent processes, we have to somehow lock the exchange bus to ensure data consistency. Intel CPUs provide automatic cache coherency through the MESI protocol, so when you simply change data in one CPU, the change is automatically propagated for you to other cores. This incurs overhead, so we’d better change shared data as rarely as possible. And this is exactly what multiplexing message exchange is about: to share the costs, we lock the exchange bus from 1,000 to 10,000 times a second. This yields pretty good performance and acceptable processing latency (1-2 ms per request).

This concludes the second part of my talk. Stay tuned!